Reflecting on my First International Conference

Sofia Watt Sjöström

Sofia Watt Sjöström is a Senior Editor at the McGill Journal of Sustainable Development Law, as well as the Editorial Officer for its partner organization, the Centre for International Sustainable Development Law. Before law school, she completed a DEC in Liberal Arts at Marianopolis College.

Given that COP15 was the first international conference I attended, doing so opened my eyes to the challenges and opportunities this kind of event represents. As an international, multidisciplinary event, COP15 brought together incredibly diverse perspectives on natural biodiversity. This has real benefits for learning and sharing information. It also feels poignant given that biodiversity loss knows neither national, nor interdisciplinary, borders.

As a student, I felt intimidated and overwhelmed at first. It took me minutes to even step into a conference room by myself. However, I was struck when an Elder at that side event began with, “I am not sure if this is what I am supposed to say here…” She was there to offer wisdom, yet she, too, felt uncertain and out-of-place. Many people at COP15 felt this way. My own malaise paled next to that of foreign visitors grappling with new customs, language, and food.

Yet feeling challenged can be a good thing for learning—law school is a case in point. COP15 bringing together many different perspectives that might not otherwise have met felt rich and exciting as well as challenging. Side events convened Indigenous voices, lawyers, consultants, scientists, and more. Just as biodiversity transcends disciplines and departments—knowing for example no distinction between “societal” and “economic” concerns—so, too, must anyone determined to fight biodiversity loss transcend these silos. Even the distinction between COP27 and COP15, climate change and biodiversity, is artificial in a context where environmental issues are inextricably linked—therein the need for “nature-based solutions” to climate change, preserving both biodiversity and the climate. Biodiversity also transcends human territorial boundaries, as an inherently international issue.

Ironically, I saw the benefits of international discourse most clearly at a talk I attended about biodiversity restoration at a local level. Sudbury, an Ontario town once infamous for pollution, successfully reduced its sulphur dioxide emissions by 98% over 45 years, improving air quality and allowing endangered species to return to the wild.[1] It did so because mandatory legislation forced local mining companies not to shut down, but reduce their emissions, actually capitalizing on useful by-products and increasing yields. What an exciting success!

However, there is a major caveat: although Canadian mining companies have lessened their impact in places like Sudbury, they continue to do great damage in other countries. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (“DRC”), Canadian-owned companies have displaced local populations and undermined their human rights.[2] We cannot be complacent and content ourselves with Canadian success stories. Not only is biodiversity conservation a global issue, but when we are talking about Canadian companies in other countries, it is shameful that this gets swept under the rug. At COP15, representatives from DRC thankfully spoke up to prevent this. Their voices exemplify why it is critical to have diverse voices at the table.

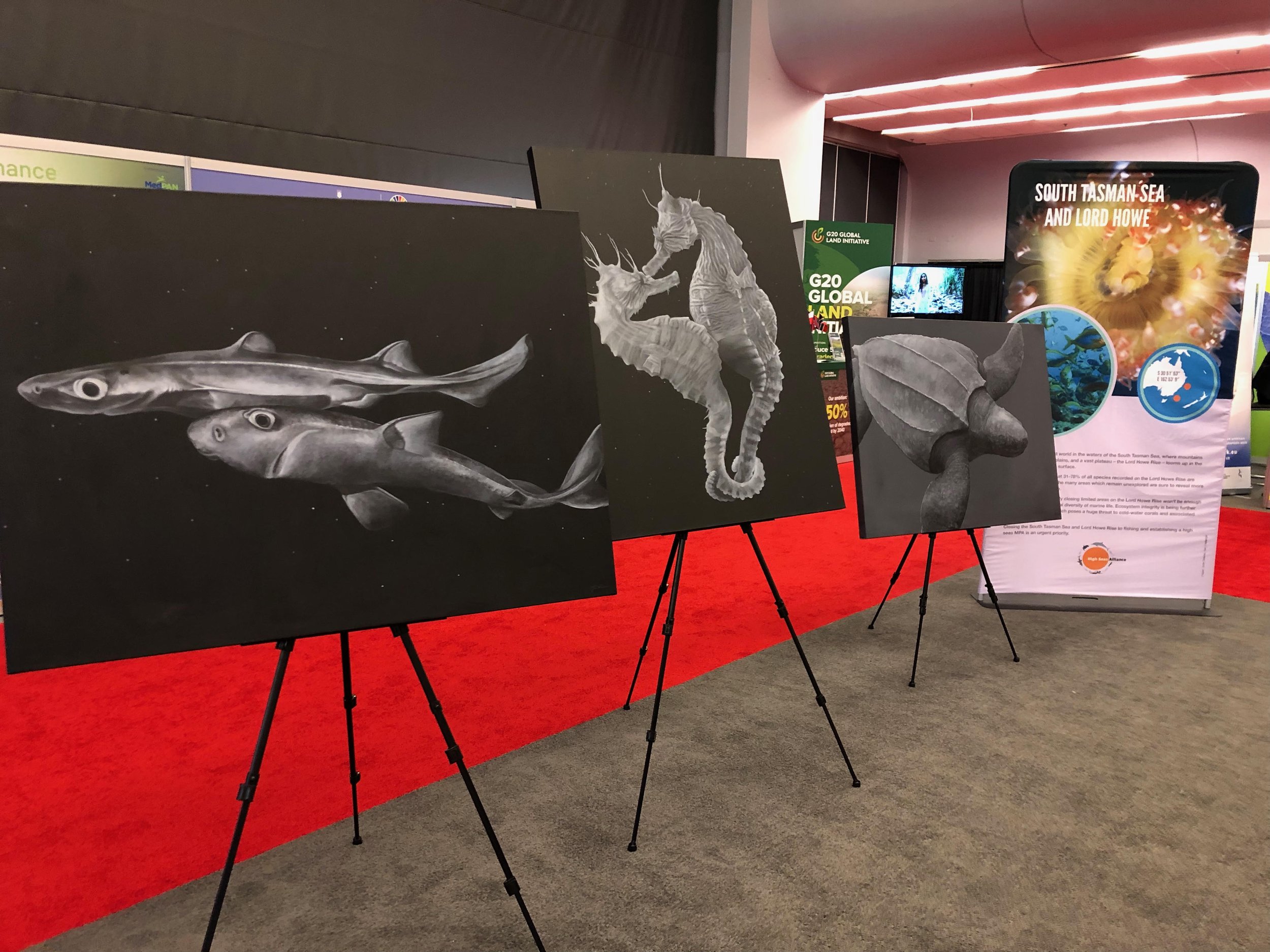

COP15 also recalled to me one of my first loves. As a child, I watched excessive quantities of nature television. Today, nature’s strange marvelousness, and the sense of wonder it provokes, brings me back to that time. It reminds me of what I’m striving to preserve in pursuing environmental law. In COP15’s main auditorium, there were booths showcasing, for instance, wildlife from Madagascar, the most biodiverse country in the planet, and Turkey, soon to host COP16. I also enjoyed keepsakes such as a Chinese wildlife view-book with pictures of species from across the globe.

In sum, COP15 opened my eyes to benefits and drawbacks of international conferences. Although there is irony in consumerism and air travel at an environmental conference, I learnt from gifts like that view-book, and, certainly, the international travellers. Given that I was only able to attend a few days, I presume the benefits were still greater for many others. International conferences may not be effective in every way—local action is also crucial—but they are unique opportunities for discourse and learning from diverse perspectives. At COP15, this may even have been pivotal to the final agreement’s unprecedented inclusion of Indigenous peoples.[3]

[1] See “Global Lessons from the Sudbury Story: Laurentian University Presentation for COP15: Dr John Gunn” (19 December 2022), online (video): Youtube <youtube.com/watch?v=mR0XCV2TUfE>.

[2] See e.g. Sarah Gale, “Banro Corporation in the Democratic Republic of Congo”, Mining Watch Canada (10 January 2020), online: <miningwatch.ca/blog/2020/1/10/banro-corporation-democratic-republic-congo>. For information pertinent to law around Canadian mining companies in Africa generally, see also Professor Sara Ghebremusse’s work, notably her talk for this journal (not yet published online).

[3] See Patrick Greenfield & Phoebe Weston, “Cop15: key points of the nature deal at a glance”, The Guardian (19 December 2022), online: <theguardian.com/environment/2022/dec/19/cop15-key-points-of-nature-deal-at-a-glance-aoe>.